Driest year on record

Rain not enough to hold off water woes

While valleys flood, snow pack drops to 20 percent of normal thanks to warm rains

The North Umpqua is full to the brim, the ground is soaked and it would seem that any thoughts of a drought must have vanished with the rain and snow of the last several weeks. But this is an illusion, a magic trick performed by nature. The drought is still here, the water table still perilously low, the snow pack in the mountains dangerously thin.

“We would need three above-average months in a row to get anywhere close to normal,” Kathie Dello, Deputy Director of the Oregon Climate Service said. “The importance of the snow pack for recreation and water supply . . . everyone is looking to the mountains.”

National Weather Service Meteorologist Ryan Sandler agreed.

“The Rogue-Umpqua basin is only at about 28 percent of normal snow-water equivalent. The long-term outlook is not good. It’s definitely better to have wet weather than dry, but next week the snow levels will be high, above 7000 feet. The ground will be saturated, the reservoirs will fill some, but the snow pack could actually melt,” Sandler said.

In Oregon, the drought is affecting a wide range of individuals: farmers, loggers, fishermen, and snow enthusiasts are all worrying about the lack of water. The Willamette Pass ski area has been open only intermittently. Hoodoo Ski Resort had its latest opening in 50 years, and the Mt. Ashland Ski area [as of this writing] still has not opened.

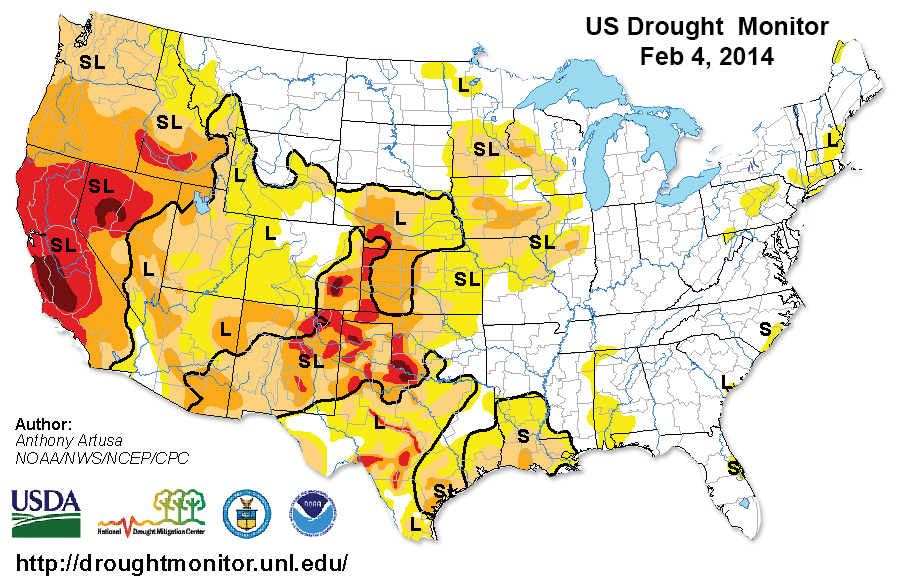

Chris Lake, director for the Southern Oregon Wine Institute, is also concerned about the lack of water. “We are seeing significant drought conditions throughout the West. It’s as dry as it’s been in 150 years. We depend on sufficient rainfall and water in the ground to sustain the vines. Wineries should anticipate less fruit coming off the vineyards.”

Douglas County water master David Williams is cautiously optimistic.

“The short-term forecast looks promising,” Williams said. “If in fact the high pressure system broke down, we could expect our fair share of rain- and snowfall, maybe 80 to 90 percent of normal. If the high pressure system set up again, we may be looking at 40 to 50 percent of normal stream flow.”

California is seeing the worst of it. Rural cities are perilously close to running out of drinking water, the snow pack in the Sierra Nevada (as recently as Jan. 30) was at only 12 percent of normal, and major fires have already broken out in Southern California. Paleoclimatolgist B. Lynn Ingram from the University of California at Berkley recently analyzed data from previous centuries and believes that this drought may be the worst in 500 years.

Oregon and Washington, while not reaching the near-apocalyptic levels of California, are still feeling the effects. Oregon’s snow pack is now at 20 percent of normal. The recent storms should have bumped that number up, but not nearly enough. Water in reservoirs across the state are at 60 percent of normal.

Sandler said that this current drought crisis is one of the worst on record. “The water levels are lower at this point than they were in 1976, 1977 [when one of the worst all-time droughts occurred.] It rivals 1976, 1977 as one of the worst in people’s lifetimes.”

Dello also believes that this drought might be one of the worst.

“We’re looking at one of the driest starts to the water year on record. In some places, it is the driest start on record. Last week was a blip. We need a lot more.”